Many League of Legends players will claim that the results of a match are determined during the champion select screen. A successful team will boast players with high APM (actions per minute) and vast knowledge of not only their own champion mechanics, but also how they function between their teammates and enemy champions. The developer of League, Riot Games, is a strong proponent of supporting the game as an e-sport and in general, to have the game be played competitively. An element, or more so, a requirement of a successful e-sports team is to master the inner workings of the game, not only the rules, but how your opponents and teammates work within the affordances of the game.

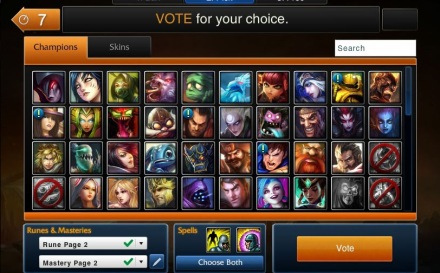

The in-game tutorials in most games provide the player with all the information needed to play the game. League instead demands a kind of play known as theory-crafting outside of the game. There are currently 124 playable champions in League of Legends; to be able to play at the professional level, players must conceptually and practically understand the affordances of most of them at any given time. Not all the champions are selected for games equally at any given time and balance changes and regular updates often promote cycles of popularity among the roster. Riot will make balances changes based on player feedback, individual champion win and pick-rates to make sure no single champion in dominating play. It’s in Riot’s best interest to prevent this from happening because it is unappealing to players to have to fight for one champion and for audiences to see a variety of team compositions during play. Anyone who is serious about League will keep up with the patch notes from the game or tune into pros streaming their practice games on the Twitch streaming website. It quite frankly, takes a lot of reading and researching to keep up, but it’s not simply enough to read the literature. Champion preference often takes into account current popular strategies in the game (or, “meta”) along with playstyle preference. It can be as general as melee vs. ranged skill preference all the way attack timings and movement patterns. Of course, champion prefer does also come with practice: players “get a feel” for the movements. It is often encouraged for players to play 50+ (at 30 minutes- 1 hour long each) matches with a single champion before attempting ranked (competitive) leaderboard play. The dedication it takes to become proficient in League is an immersive experience in that the player needs to think, read and play according to the rules (and updated rules) of the game.

In Homo Ludens, Huizinga discussed the nature of war and play as a cultural function even before civilization (89). While the concept of “War games” certainly persisted long before Huizinga, we can still think about how culturally, this concept permeates through a multitude of similar, more modern activities. In gaming there is certainly more explicit war games based on real-life armies and battles, but we tend not to think of games such as League of Legends as a part of this grouping due to its fantasy setting and emphasis on individual champions as opposed to groups of armies. However if we move past the fixation on large groups fighting in game, we may want to consider the ways in which players plan for a League match to be indicative of a war game. Huizinga states that “competition is not only ‘For’ something but also ‘in’ and ‘With’ something” (51-52). To perceive League as a game about destroying the enemy team’s Nexus overlooks the smaller accomplishments required to get to the end goal both in-game and out of game. Along with having the knowledge of individual champions, more skilled players boast a high APM (actions per minute) skill to be able to pull of more complicated maneuvers and kill opponents faster. Additionally, communication via headset and in-game pings assists in gathering teammates together more quickly and effectively. Thus following Huizinga’s standards of competitive play, League is a competition for destroying the nexus, in computer and verbal mastery and with a group of five players who have a shared knowledge of the game, their team and their opponents.

Banning

Banning disrupts the flow of the game either by recognizing that a particular champion needs to be nerfed next patch, that they directly counter one of the banner’s preferred roles or to prevent trolling. In ranked play each team leader (which is chosen at random before the champion select screen appears) must ban three champions with each side picking one at a time. The purpose of the banning phase is to eliminate choose-able champions and to customize the match to suit the strengths and weaknesses of each team. In professional play, teams often know their enemies best champions and will likely select bans tailored to the enemy. In ranked play, it is virtually impossible to know this information as you are always matched up with strangers so bans in regular ranked play consist of champions who are considered over-powered (OP) as judged by the players and the current meta. Riot will look at an individual champion’s ban rates as a factor for determining later patches or when to completely rework an entire move-set (kit). As stated earlier it is in Riot’s best interest to keep League updated with new content and patches. New champions are introduced to the game once or twice a month, which expectedly changed how each current champion responds to that matchup. Online communities such as Lolking.net host champion guides in which the writer can go into detail about how that champion fares against every other champion in the game. To have the meta change so often requires a dedicated team of developers but also a community who is willing to stay updated and communicate with Riot to make sure how metas change.

Spoil-Sports Ruin Everything: When Champion Select Goes Wrong

There are often two reasons why a game can go horribly wrong during champion select: A failing internet connection and trolls. When a game relies in the stability of 10 players’ internet connection at any given time, there is bound to be problems. Disconnections and lag can cause people to make mistakes, not be able to type in the chat box and even select the wrong champion. According to the meta, a non-balanced team (one that does not have an equal amount of damage output, defense, healing and so on…) can be easily exploited by the enemy and can have detrimental effects to the outcome of the game. During champion select, player will communicate to each other as to which “lane” they would like to play in. Summoner’s Rift has three lanes: Top, Mid and Bottom along with a champion in the Jungle area who moves in between each of the lanes. These lanes coincide with preferred champions as each one has their own optimal lane positions; while there can be overlap the meta normally dictates where each champion should be going. For example, the main attack damage champion (the ADC) always go bottom lane with a support character because they are weaker in defense and need the support to help them. Thus, the dynamic of such a lane can be disrupted if two ADCs are picked and go bottom, for example. The expected shared knowledge of anyone who enters a ranked game dictates the behavior of champion selection. Riot has even spoken out about regulating who gets to pick their champion of choice and when. When players do not get along or have an argument over the lane selections, spoil-sports may emerge in the game. Huizenga discusses the function of the spoil-sport as someone who breaks immersion and the flow of play. He states that, “By withdrawing from the game, he reveals the relativity and fragility of the play-world” (11). Someone who doubles up on a lane, bans a champion someone requested to play as or prevent other players from strategic plays and/or enjoying the game do not play by the rules, not mechanically of course, but socially. The game allows for deviance in the fact that the player can break the meta or not listen to their teammates. Csikszentmihalyi describes flow as “the state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience itself is so enjoyable that people will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it”. This type of deep focus during a game is common, especially in many professional gaming sessions where cameras, audiences and the pressure of winning can all impact player performance. Csikszentmihalyi very abstractly, discusses the otherworldly state of flow in practice:

every flow activity, whether it involved competition, chance, or any other dimension of experience, had this in common: It provided a sense of discovery, a creative feeling of transporting the person into a new reality. It pushed the person to higher levels of performance, and led to previously undreamed-of states of consciousness. In short, it transformed the self by making it more complex. In this growth of the self lies the key to flow activities.

However this can also occur in any sort of game non-professionally or even non-competitively outside the ranked mode especially in League where player retain and execute so much knowledge that often they forget they are playing with other human being behind the screen. What Csikszentmihalyi fails to mention is how flow experiences may create happiness for the individual but potentially at the expense of others. Culturally, this may be regulated through the Tribunal systems but the prevalence of hegemonic masculinities often gets in the way of controlling “hurt feelings”. After a game, players can report others for a list of offenses varying from “Refusal to Communicate” to “Verbal Harassment” more often than not, the report button is often skipping in the end-game screen. Even though the game cannot prevent a person for committing these crime directly in that they would inhibit players from the natural progression of meta over time, Riot can still implement a means for the larger community to decide what behaviors in the game are acceptable, just like in any other game or sport.

The proceedings of a League of Legends match can be tied back to early theories of play especially when considering war games. The hostility and intensity of planning and executing effective team dynamics is a symptom of the immersive experience and the expectation of others to share in such. If the player does not live up to the expectations of the experienced teammate, then they often become subject to scrutiny. While the flow of champion select as-designed occurs naturally based on the genre and visual cues from the game, the chat feature is less regulated, making way for spoil-sports who are either too immersed or not immersed enough to be regulated by the social rules of the game. There has been talk of seeing e-sports take the Olympic stage, but a game like League needs time to help a shared cultural understanding of the proceedings without the common hostility.